In which an ordinary working day for an antenna technician becomes a very exciting field trip for an artist with a camera, in the hills above McMurdo Station.

Read MoreTemperatures

Photos can tell you what Antarctica looks like, but what does it feel like? Can this most foreign continent be understood in the context of anywhere more familiar?

Read MoreMcMurdo Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is one of the most important holidays in the US, so it is an important day on the McMurdo calendar as well. In civilisation, it’s usually celebrated with big family gatherings on the last Thursday of November, making for a four-day weekend typically filled with football and Christmas shopping. At McMurdo there is so much that needs to be done in such limiting circumstances that a six-day, 60-hour work week is standard; taking three whole days out of the peak season would be unconscionably profligate, so instead they celebrate Thanksgiving on the following Saturday and luxuriate in a rare two-day weekend.

Growing up hundreds of miles from extended family, and being a fan of neither football nor shopping, the primacy of the holiday had mostly passed me by; in the years I was an adult in the States, I usually spent it with other ‘Thanksgiving orphans’ doing something atypical. Perhaps the most important Thanksgiving of those years was the one I spent in New York on the promotional gig for Princess and the Frog, because that’s where this adventure started. I was working that day, but they catered a turkey dinner for us at the venue, and I ate my roast and sweet potato off a paper plate backstage while reading The Worst Journey in the World for the first time. Exactly ten Thanksgivings later I was in Antarctica, where it all took place.

The early expeditions knew the importance of good food. Obviously as a source of energy, getting sufficient calories was a prime concern, but when one is starved of most of the pleasures of life, food takes on a great emotional significance as well as biological. The cook on the Discovery Expedition was so bad he was sent home when the relief ships came. Both Scott and Shackleton learned from this experience – Shackleton brought a wide variety of ‘luxury’ foods on the Nimrod Expedition, and Scott made sure that the cook on the Terra Nova could turn his hand to making ordinary meals delicious and extraordinary foodstuffs palatable.

The biggest event in the Heroic Age culinary calendar was the Midwinter Feast, which took on the significance of Christmas, for not dissimilar reasons of brightening the darkness and cold. At Cape Evans, Midwinter 1911 began with a multi-course meal replete with sweets and alcohol, followed by toasts and the presentation of an ersatz Christmas tree bedecked with amusing little presents for everyone, and finally the table was collapsed and cleared away for a slideshow and a dance. Cherry-Garrard declared “It was a magnificent bust.”

American Thanksgiving falls during the Antarctic summer, so unlike the Midwinter feasts of yore, a lot of the activities are outdoors, and involve the New Zealanders from around the corner at Scott Base as well. There is a manhauling race (which the Kiwis always win) and a foot race called The Turkey Trot, which runs a loop around Cape Armitage and back through The Gap. Costumes are not compulsory but have come to be expected, so I went to take photos.

A runner arrives

The rainbow assembles – the figure centre-right with the splayed legs is wearing a turkey costume.

And they’re off!

Some of the first successful returnees

Being an open day, there was an uptick in tourism from the New Zealand side as well:

McMurdo’s mighty kitchen crew, with extra volunteer labour, had been working to prepare the feast all week. There were a number of scheduled seatings throughout the day, to regulate flow and make sure everyone had a table. I met with my coordinator’s other ducklings outside the Galley at 4.30 for the 5.00 seating, and when we were allowed in we got to see how the rather utilitarian Galley had been done up as a nice buffet, with tablecloths and everything.

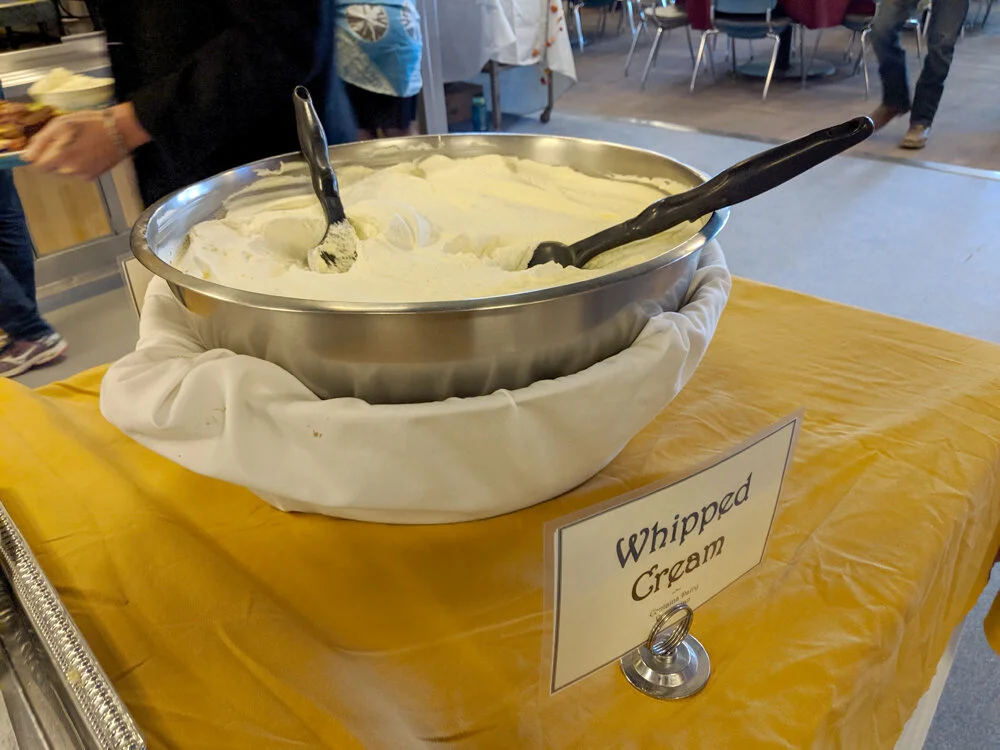

I was particularly amused by this offering, given that Capt. Scott’s great food craving from the southern journey on the Discovery Expedition was a great big bowl of Devonshire cream:

It was actually cream, none of that Whipped Topping stuff.

We found our seats and tucked in. Most of my tablemates were British and it was their first experience with some American Thanksgiving standards – the pecan pie in particular got an enthusiastic vote of confidence.

You can’t see it in this photo, but the group behind us, to the right of the frame, had had some orange trays made (vs the Galley’s usual blue) that read ‘Make Antarctica Great Again.’ As far as anyone could tell, they were not being ironic. In a community dedicated to science, where even the dishwashers are likely to have a university degree, there is a certain amount of tension under the current US administration. Government support makes McMurdo possible, but the anti-science, anti-conservation tilt of The Powers That Be render it precarious, and the MAGA crowd at Thanksgiving were the subject of much anxious whispering over the next few days.

Exuberant after-dinner larks are as much a feature of Antarctica now as they were a hundred years ago, only with the advantage of electricity they are now quite a lot louder. I am not one for crowds or noise, and had had quite an intense week, so my plan was to make for the dormitories before the impromptu nightclubs opened, but I did stop in to see the one my friends had been setting up. They were down to get some specific footage for a documentary series, but the weather had not been on their side, so to fill their days they had put a great deal of time and effort into converting the gym into a dance club. Regrettably I don’t have any photos of it, but they did a really outstanding job, and the verdict the next day was that Club 77° was the best venue in town.

For my own part, I was happy to hit the hay.

View from my dormitory window

If you’re curious about what goes into feeding Antarcticans, PBS’ Nova did a great little feature on it here:

And yes, the pizza really is that good.

Views From Crary

The Crary Lab, where I had my office space, was not short of cognitive dissonance: the building was strongly reminiscent of the late-80s built-in-a-hurry school buildings where I’d spent most of my prosaic childhood, but through the windows was a view that was not only heavenly but seemingly teleported from Ponting’s photos. It was two breeds of familiarity clashing heavily together.

Read MoreBasler to the Beardmore 4: And Back Again

Having had the grand tour of the Beardmore Glacier, we set our course to return to McMurdo, via one last historical waypoint …

Read MoreBasler to the Beardmore 3: The Beardmore Glacier

On leaving CTAM our practical business was completed for the day, so it was time at last to do some sightseeing. We were near the top of our glacier as it was, so we flew to the southern end of the mountain range to our east and then turned to round it, and suddenly, the vastness of the Beardmore Glacier was revealed.

Read MoreBasler to the Beardmore 2: Errands

On this flight to the heart of Antarctica, I was only a hanger-on. We had two errands to run before entertaining me and my historical interests. The most important one was restocking a fuel depot, but we had also been asked to investigate an abandoned geological camp in the Transantarctic Mountains.

Read MoreBasler to the Beardmore 1: You See a Plane, You Take It

When planning my research trip with the Antarctic Artists & Writers Program, I had to make a wishlist of places to visit. One of the more important ones was the Beardmore Glacier, the route by which Scott and his men climbed from the Ross Ice Shelf (or, as they called it, the Barrier) to the Polar Plateau.

Setting foot on the Beardmore was too big an ask, but there are regular LC-130 flights between McMurdo Station and the Pole which traverse the Beardmore en route. We planned to put me on one of those, where I would snap as much as I could from one of the small windows as we flew.

What actually happened turned out to be much, much better than that …

Read MoreScene 5: Int. Cape Evans, the Opium Den

We conclude our tour of the Cape Evans Hut with a visit to The Palace, the fanciest bunk in the place, and its neighbour the Opium Den, which reminds us why the modern translation of such a place is ‘crack house.’ It was nicer in 1911.

Read MoreHappy Birthday, Captain Scott!

On June 6th, 1868, Robert Falcon Scott was born near Plymouth, in southwestern England. June 6th, 1911, he celebrated his forty-third (and last) birthday with his expedition members in their hut at Cape Evans.

Read MoreScene 4: Int. Cape Evans, Science Corner

One of the other dark secret corners of the Cape Evans hut, the labs were where the biology, meteorology, chemistry, and physics of the Terra Nova expedition took place. Also included is the photographic darkroom where a different type of science was practised by Herbert Ponting.

Read MoreScene 3: Int. Cape Evans, Aft Cabins

The commanding officers of the Terra Nova Expedition – Scott, Wilson, and Evans – had their lodgings in the northeast corner of the hut. They had a little more space, and a little more privacy, but it wasn’t luxurious. Come follow me into the dark corners …

Read MoreScene 2: Int. Cape Evans, The Tenements

In the officers’ quarters, five rickety bunks were crammed into the starboard side of the hut. This cubbyhole was home to Apsley Cherry-Garrard, Birdie Bowers, Titus Oates, Cecil Meares, and ‘Atch’ Atkinson, and thanks to its crowded slum-like appearance, was dubbed ‘The Tenements.’

Read MoreScene 1: Int. Cape Evans, Men's Quarters

I have walked around this hut many, many times in my mind, aided by historical photos and some modern ones, so actually stepping through that door and seeing it for myself was a very emotional experience. The wash of feelings was cut short, though, by the sheer stimulation of recognising all these things whose stories fill my brain. Please let me show you around and tell you some of them.

Read MoreNova Goes Antarctic

One of my favourite TV shows growing up was PBS’ NOVA series, so it was a real joy to find that they’ve done a YouTube series based at McMurdo, talking about the science there, but also giving you a pretty good sense of what it’s like to live and work with the USAP.

Read MoreCape Evans, Exterior

I have enough photos of the interior of the Cape Evans hut to fill twenty posts – there will probably be four – but to get a good idea of the context for the hut, let’s do a little exploring outside, first.

Read MoreThe Road to Cape Evans

Having done Sea Ice training at last, I was clear to head out on snowmobile. My coordinator’s intent had been to do a ‘shakedown’ one day – a practice run, to get used to the vehicles, how to load and tie down the sledge, a chance to get things wrong when it doesn’t really matter – and go to Cape Evans the next, but the morning of the shakedown she said ‘It’s a beautiful day, let’s combine the two.' Thus was initiated a de facto rule of my month in Antarctica: One Must Only Ever Go To Cape Evans By Surprise.

Read MoreSea Ice: Crack Safety

Water ice is a curious material: though apparently a solid, it can nevertheless flow, bend, and wrinkle. The mile-thick Antarctic ice cap is very gradually flowing out to the edges of the continent, through the mountains in glaciers, and when those glaciers leave their channels they spread out like hot fudge (only much slower).

Most of the time, though, what ice does is crack. In a glacier this makes a crevasse; on sea ice, it’s a short trip into some very deep, very cold water. When you’re travelling across the sea ice, it’s the cracks you need to worry about, and once you start looking for them they are everywhere. This would be enough to put off a cautious traveller but most of them are relatively harmless: the requisite sea ice training helps you determine just how risky your movements are.

First, you have to learn about how sea ice forms. You will not be surprised to learn that this happens when liquid water meets cold air.

The nice flat young sea ice is never allowed to let be, though – forces in the water underneath and air above, or even changes in temperature, put strain on it, and to release the tension it cracks.

Like a broken bone, or a fault line in rock, once ice has broken it is more likely to break again at the same place, so being aware of cracks will show you where you ought to be extra careful. Simple cracks are usually one-time releases of stress, and once refrozen rarely pose a risk, but you need to be wary of working cracks because they have shown they are unstable and their condition might change without notice.

Because they are much larger, working cracks tend to be more visible, sometimes even when the sea ice has a layer of snow on it. Pressure ridges show up very well and are a useful indicator that the ice has been moving around. Here is a very small pressure ridge just off McMurdo Station:

The snow blowing across the sea ice has been caught and drifted by the protrusions of the pressure ridge. When you have an recessed working crack, instead of a pressured one, the crack gathers the snow and shows up that way.

When you come across one of these, you have to find out what is going on under there before you know it’s safe to cross, so the following procedure is taken:

Here is the crack you saw earlier, with its snow-covered secrets revealed.

Each vehicle has different parameters for what a ‘safe’ crack is. Most tracked vehicles – snowmobiles, Hagglunds, etc – can safely cross a crack whose width is 1/3 the length of their track. So, if your snowmobile’s track is 90cm long, you can cross a 30cm crack even if it’s open water. (I would balk at doing it, myself, but it is theoretically safe.) You measure the maximum width of the crack to see if it’s within your vehicle’s safe crossing threshold. If it isn’t, it might still be safe to cross after all, but you will need to do some more measurements to find out.

Measuring sea ice thickness is great because you get to use a) a power auger and b) my favourite device in the Antarctic toolkit.

You drill either side of the original crack to make sure the ice – which is weakest here, remember – is within the specified necessary thickness to support your vehicle. You don’t have to memorise this number because your teacher has given you a laminated card with a table of all the vehicles and their requisite ice thicknesses. Your job is not to lose the card.

Once you’ve ascertained that the ice either side of the widest crack is safe, you find a point within the safe crack width for your vehicle and measure the ice there. So, using the example from before, if your snowmobile with 90cm tracks comes up to a 45cm crack, you cannot cross, so you find a point 30cm (the safe width) from your side of the crack and measure the thickness of the ice there.

If the ice at the safe width is thick enough for your vehicle, then that becomes the effective width of the crack, and you can cross over. The actual width is the objective total width of the crack, whereas the effective width is the width that matters to you practically.

The reason you have to drill again at (3) instead of just subtracting the change in surface elevation from the measurement you took at (2) is because of the irregularity of the underside of the ice. You don’t know if there will be a big lump of nice solid ice there, or if it will be a surprisingly thin patch, so you have to check. For this same reason, you can’t measure a crack in one place and cross in another, because conditions along the crack can change completely in just a few metres.

Part of the job of the Sea Ice Master* at McMurdo is establishing ‘roads’ for vehicles to take to regular destinations (e.g. Cape Evans, the seal camp at Turtle Rock, Penguin Ranch, etc). Usually the ice is thick enough that these roads can go more or less directly there, but this year the ice formed so late, and in some cases was so choppy, that the roads snaked and dog-legged all over the place to find safe crossings. On top of that, the early summer had been exceptionally warm, and there was a great deal of nervousness around just how long the sea ice would be traversible at all. Luckily there was a cold spell just before I arrived, which bought enough time for me to travel to Cape Evans. In my last few days at McMurdo the sea ice did finally get closed to all traffic and the flags marking the roads were brought in, so it was a close run thing.

*not the actual job title, but should be

Sea Ice: The Basics

Antarctica is, as we all know, a continent of ice. But the ice isn’t just the ice caps and glaciers on the continent itself – it extends off the coast in all directions as the Southern Ocean seasonally freezes over. It provides a very convenient way of getting to places which would be cut off by water otherwise, but before one can travel on the sea ice, one needs to understand it. The practical skills of sea ice safety are predicated on an understanding of how the natural system works.

Read MoreArrival Heights

One day, an afternoon’s plans got cancelled, so I took a nap instead in order to take a hike in the midnight sun. The light was indeed better at midnight, plus I learned an important thing about fluid dynamics, all while walking (and scrambling) in some historic footsteps.

Read More