Now that you have filled in your name, date, and time of entry, you can begin to explore the place properly. You are standing in the largest ‘room’ of the building, the wider arm of an L-shaped space which wraps around the improvised inner compartment. This was where the Terra Nova men slept on their way back from the Depot Journey, where their sleeping bags were turned into a ‘snipe marsh’ by the meltwater from the ceiling. For reasons lost to history, it was known as ‘Virtue Villa.’

Read MoreThe Story of the Discovery Hut

The Discovery Hut was one location shared by the four major Heroic Age expeditions in the Ross Sea area. Visiting was the pinnacle of the sensory overload of my first 36 hours on the continent, not least because the grubby old hut is one of the least well documented sites, so most of it was completely new to me. But I knew the stories behind it, so I share those with you now, so you can see it through the lens of history as I did.

Read MoreInduction McMurdo

Arriving at McMurdo is kind of like diving into your first week at college. You have a series of orientation sessions, a bunch of classes in different buildings with random numbers, and you meet a lot of new people with names and roles that are hard to keep straight, while juggling extracurricular activities and the institution’s intranet. On top of this are Antarctic-particular rules around getting your food and sorting your garbage, and adapting to the unwritten conventions and jargon of the society. It’s exhausting and overwhelming but also really fun.

Read MoreLong Trail to McMurdo, Part 5: Getting There

At long last, I board an enormous windowless plane, and after five hours of noise and vibration, step out in Antarctica.

Read MoreLong Trail to McMurdo, Part 4: The CDC

Between arriving in Christchurch and departing for Antarctica, one is issued a great pile of cold-weather clothing from the USAP’s depot, including the standard heavy parka known as Big Red.

Read MoreLong Trail to McMurdo, Part 3: Christchurch

The last time I was in New Zealand, I was making what I thought was the trip of a lifetime. It was January 2018, and, assuming a trip to Antarctica was unlikely, this was the last gap I had to fill in my research. I flew from Los Angeles this time rather than Vancouver, on a ticket bought for me by the US Antarctic Program, en route to that destination which, last time I was here, I was sure I would never reach.

Read MoreLong Trail to McMurdo, Part 2: LA

From Vancouver, I flew down to LA, where I was to spend a week before catching the USAP flight to Christchurch. That flight had been the source of some anxiety. I couldn’t be issued a ticket until I medically qualified, which I did in September; the ticket was not forthcoming, however, and as the clock ticked down to my departure from the UK I was assured that it was in process and that I should expect it three weeks before the planned flight date. When this didn’t happen I inquired, and my coordinator said it was running at 10-14 days prior now. Now in Vancouver. those dates passed still with no ticket, but I was contacted to re-confirm my travel details, so at least I knew I hadn’t been forgotten. At last, the morning of my afternoon flight to LA, it arrived. I was booked a day earlier than planned, due to a shortage of tickets on the original date, but an extra day in Christchurch would be to my advantage so that was all right.

I lived in Los Angeles for 5½ years, working at Disney Animation. It was a very educational time if not a terribly happy one; by the time I left I needed a good deal of healing, which thankfully my next job, and then my first year in the UK, provided. It’s strange coming back, because the sights and smells ought to be so familiar, but my time here has been tidily packed away in its own little box, and I’ve become so happily bedded in my new home that I feel detached from that whole period, as though it happened farther away and longer ago than the second-hand Antarctic history that’s so fresh in my head.

This visit was particularly interesting in that I jumped back into the animation world with both feet. My sister threw a going-away party and invited a load of friends from Disney days, most of whom I hadn’t seen in six years, some of them not for ten. It was really good to reconnect and catch up on what we’d all been up to in the meantime – many of them had been to the Frozen II wrap party the night before – and was the cause for much reflection on ‘what if’s. My sister has stuck with the animation industry and made a successful career of it, and all these friends were doing well on their respective tracks. I had never thought I would be tempted away from animation: I wasn’t happy in LA, but I am happy at a desk drawing other people’s ideas, which is generally a recipe for contentment in the industry, wherever I fetched up. And yet there I was, on my way to Antarctica, and they on their way to an early night before their regular salaried jobs the next day. My next day, I accompanied my sister to her high-level job at a prestigious studio, and had a fine free lunch with yet more old friends living their successes, before she drove me to buy stamps to reward my precious crowdfunders who keep me in my rented room and fill my cupboard with potatoes.

When you work someplace like this, you’ve probably Made It.

I often say my twenty-five dead guys ‘rescued’ me. Certainly my pursuit of this story gave focus and direction to my exit from LA, but I was on my way out anyway. One could make a convincing case that I was ‘rescued’ from professional advancement and financial security, which hardly seems like a rescue at all. And yet, if the tables were turned, and I, a content and well-respected animator in 2019, were attending the going-away party of a friend on a mad adventure to the ends of the earth, I know I would be questioning my life choices. To paraphrase Mary Oliver: what would I be doing with my one wild and precious life?

Everyone has to answer this question for themselves. For some, undeniably, achievement and comfort are the paramount goals, and there is nothing wrong with that. I, however, seem to have inherited the restless gene that sprayed one side of my family across North America and the Pacific Rim. The small taste of accomplishment and comfort I did have worked for some time to anaesthetise me to the need for something else, but not for long. In a way that must be hard for many to understand, I knew I couldn’t rest happy until I’d at least tried to bring this project into the world, whatever sacrifices it entailed. Though it may not look like an improved condition from the outside, I was rescued inasmuch as I was removed to a path to my own eccentric brand of happiness, for which I am ever grateful.

My time in LA happened to coincide with Dia de los Muertos, the Mexican festival of the dead, in which departed loved ones are commemorated and one is confronted with the inevitable finitude of life. Buddhists believe that one must acknowledge and accept death in order to live more fully in the present. My time in the company of people who are all dead, now, but especially those who didn’t expect to die when they did, has been an invaluable education in the importance of doing the most with the time that is given you. These ideas are present in historical Christianity, but modern Western culture has made death such a taboo that the urgency of living while you can is more or less lost: if you don’t think about death, it won’t ever happen, right? Perhaps we would do better to remember that all of us will exit this life, perhaps much sooner than we think. Whether you acknowledge death or refuse to think about it, it will, inevitably, find you. What will you regret not having done with your wild and precious life?

In a subtle and slow-motion way, the two weeks leading up to my departure for the South have been my life flashing before my eyes. I have been lucky enough to have lived several lives in my thirty-some-odd years, and I’ve revisited a few of them on this trip so far. Where it takes me from here is anyone’s guess, but I find myself in the highly unusual position of not regretting anything important in what’s come before. If my plane goes down in the South Pacific, I will be very annoyed that I didn’t get to finish drawing Vol.1, nevermind the rest of the story, and would wonder what the point of it was, but I had fun doing those first 81 pages and there isn’t anything I would rather have done with that time. It’s taken a lot of hard internal work to get to that point, but it’s a good place to be.

Time and substance are irrelevant here. It will drive you mad or liberate you, or perhaps both.

By the time you read this, I will, most likely, have been in Antarctica, and am probably on my way back. People say Antarctica changes you; how will it have changed me? Will I be looking at my familiar places in new ways? Will it have changed my perspective on the people in my life? I am writing this in LA on the brink of departure and am very aware of standing on the cusp of something. The trip hitherto has afforded me the opportunity to reflect on what got me here. It has been a long and strange road but a good one, and from this perspective at least, I feel it has prepared me well. We shall see.

And I tell you, if you have the desire for knowledge and the power to give it physical expression, go out and explore. If you are a brave man you will do nothing: if you are fearful you may do much, for none but cowards have need to prove their bravery. Some will tell you that you are mad, and nearly all will say, "What is the use?" For we are a nation of shopkeepers, and no shopkeeper will look at research which does not promise him a financial return within a year. And so you will sledge nearly alone, but those with whom you sledge will not be shopkeepers: that is worth a good deal. If you march your Winter Journeys you will have your reward, so long as all you want is a penguin's egg.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World

The Long Long Trail to McMurdo

As part of the position with the Antarctic Artists and Writers, the US Antarctic Program would be flying me from the US to Christchurch, New Zealand, base for their Antarctic operations. Not being a US resident myself, it was my responsibility to get to the departure airport. As I have lived most of my life on the west coast of North America and my sister still lives in LA, that seemed the obvious departure airport; if I was going to fly all the way there then I might as well pass through Vancouver, which I still consider ‘home’ for a given value of the word. With a week visiting time in each city, it’s become a very long trip, but the week in Vancouver was very well spent and a much-needed respite after the mad rush of last-minute preparations.

It’s funny how easy it is to slip back into old shoes … I haven’t lived in Vancouver for over a decade, now, but within a few days I was back in the groove, though the weather was most uncharacteristically sunny for the time of year.

View from Lion’s Gate Bridge on my journey from the airport. It was good to see the Pacific again.

I got a sizeable portion of my polar library from this shop. I didn’t have room to take any books with me, but I checked in just to see what they might have. Do search for the elusive photos from inside and visit if you’re in town; it’s a Mandelbrot of L-Space.

Of course, it’s only appropriate that they have a vast selection of used Antarctic books …

From underneath Lion’s Gate Bridge, this time, towards Mt Baker

For a city on the far side of Canada, Vancouver has a surprising number of Scott connections. Pennell came through in December 1905, transiting between Quebec and China on Navy business. Silas Wright passed through with two of the Terra Nova’s sledge dogs on his way back to Britain from New Zealand, via a visit to his brother in Prince Rupert. He taught for a while at UBC and retired not far away. Cecil Meares is buried in one of Vancouver’s cemeteries. Capt. Scott himself was stationed for a time at Esquimalt, across the strait near Victoria, as a young lieutenant. This one, above, is more tangential, but King Edward VII did have part of Antarctica named after him; he had only just acceded the throne when the Discovery set off, and kicked the bucket just before the Terra Nova did the same. I have, myself, only recently drawn his head on some coins.

Vancouver can’t boast the astonishing fall colours of eastern Canada, but this year – hot summer, wet autumn – was pretty remarkably colourful by Vancouver standards. Here, a catalpa.

A tulip tree.

Don’t know what this was but it was lovely.

Usually when I visit Vancouver, I spend a few days with extended family on Vancouver Island. I didn’t have time, this time, but I went to Horseshoe Bay anyway just to enjoy the ambience.

A Horseshoe Bay herring gull, mourning the desertion of his patio. He didn’t take his eyes off the family eating just inside the window.

Night night, Vancouver.

Geography of the Terra Nova

While it will, of course, be tremendously emotionally satisfying to walk in the footsteps of my heroes, my real practical reason for going to Antarctica in my own corporeal form – and this specific part of Antarctica, rather than the more accessible Peninsula or somewhere much closer to home that is equally covered in ice – is to get an authentic sense of place. In order to really understand what it’s like to move around in the locations the Terra Nova Expedition called home for two years, one needs to be in that space oneself, and getting a sense of the atmosphere and conditions will contribute hugely both to understanding the history and depicting it truthfully on the page.

In order that you, dear reader, should understand what I’m talking about and where I’m going, I have put together a quick guide to the Ross Sea region.

First, an overview of the Antarctic continent. It’s really big. To get a sense of the size, it is larger than Australia; it could fit the U.S. and Mexico together; if you drew a circle around the whole of Europe, that’s roughly the size and shape of the Antarctic continent. Our action revolves around the Ross Sea area, south of New Zealand, roughly centred on the 180° meridian. The main features here are the Ross Sea, a large indent in the continent, and the Ross Ice Shelf, a floating plain of ice several hundred feet thick, which covers the southern half of the Ross Sea. This ice shelf is about the size of France, or of Texas, whichever resonates most with your personal frame of reference.

[map taken from the British Antarctic Survey website]

The detail area delineated above is the broader theatre of the Terra Nova Expedition. I will not be visiting most of these places, but it is useful for you to know them, to understand some of the events of the story.

My placenames and terminology can sometimes be 100 years out of date – I think King Edward VII Land is called something else now, and no one calls the ice shelf ‘The Barrier’ anymore – but it’s simpler for me to use the same names as appear in the records I’m studying.

The area marked ‘Bay of Whales’ used to be a definite inlet in the northern face of the ice shelf. The ice shelf is made primarily of ice flowing off the continent into the sea, and its forward face is constantly breaking away as more ice pushes in from behind, so it’s impossible to pin down permanently on a map. However, a bay was consistently found in this area, so it got a name. Many years later, Roosevelt Island was discovered, which explained the permanence of the bay – its contours might change, but as it was a result of the ice flowing around the island, the fact of the indentation there remained. Now it appears that the ice sheet has retreated nearly to the island itself, so the ‘bay’ no longer has its defining walls.

The Beardmore Glacier, which provides a broad and relatively shallow ramp up from the ice shelf, through the Transantarctic Mountains, to the polar plateau, was discovered on Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition of 1907-9. It was the obvious route to take when planning the Terra Nova Expedition’s journey to the South Pole.

One of the camps on Scott’s ascent of the Beardmore Glacier.

The main body of the Terra Nova Expedition was always going to be based on Ross Island, but a side branch was supposed to have been landed on King Edward VII Land, to the east, as this was largely unexplored. They couldn’t find a suitable landing place, and on the way back, they discovered that Roald Amundsen’s Norwegian expedition had set up their base at the Bay of Whales. It would have been awkward to have two competing expeditions working in more or less the same area, so what had formerly been the Eastern Party decamped to Cape Adare, on the west side of the Ross Sea.

But, as the story I’m telling takes place mostly in the Ross Island area, and that’s where I’ll be, let’s turn our perspective around 180° and take a closer look at that.

[base image taken from Google Maps satellite view]

Ross Island (as well as the Ross Sea and Ross Ice Shelf) were discovered in 1840 by the expedition led by James Clark Ross. Their ships, HMS Erebus and Terror, gave their names to the two volcanoes which dominate the island, and the second-in-command, Francis Crozier, had the easternmost cape of the island named after him.

In 1902, the area was revisited by the Discovery Expedition, Scott’s first. They explored the western side of the island, naming Cape Royds and Cape Armitage after senior officers on the Discovery. They spent two winters anchored in the bay between Hut Point and Cape Armitage, living in the ship, but also built a hut at Hut Point. The American base at McMurdo Station is walking distance from Scott’s Discovery hut, and if you cross Cape Armitage to a feature formerly known as Pram Point, you will find New Zealand’s Scott Base.

The RRS Discovery, icebound, with Observation Hill in the background. McMurdo Station now occupies the slope behind the ship, which Scott and his men used for ski practice.

Scientific bases, old and new.

Ernest Shackleton had been one of Scott’s officers on the Discovery; he took his own expedition back to Antarctica in 1907 on the ship Nimrod. They established their base at Cape Royds, a little more than a day’s journey north of Hut Point.

Shackleton’s hut at Cape Royds, in the midst of an Adelie penguin colony.

When Scott returned with the Terra Nova in 1911, they established a new base at Cape Evans, a landmark freshly named after this expedition’s second-in-command. This location afforded them good access for the ship, interesting features for the geologists, and a central location for their actions, but had the disadvantage of being cut off from the permanent ice shelf for a few months every year when the sea ice broke up between Cape Evans and Hut Point. The old Discovery hut at Hut Point, then, was used as a secondary base for parties travelling south.

Cape Evans, as photographed by Herbert Ponting, looking north from Wind Vane Hill

Between Ross Island and the Beardmore Glacier was established a safe and direct route, along which depots were laid at readily identifiable places. This became known as the Southern Road. It travelled southeast from Hut Point until it was clear of the protrusions on the western shore of the Ross Sea, then shot straight south until it reached the base of the glacier. The site of this bend was known as Corner Camp. Scott wanted to lay depots along the route as soon as they arrived, so that the following summer’s journey to the Pole wouldn’t need to drag absolutely everything all the way from base. The final depot in this chain was supposed to be placed at 80°S, but due to circumstances on the depot-laying journey, they had to stop just short, and it was placed at around 79°30’S 170°E. Due to the quantity of stores left here, this became known as One Ton Depot. It might be the most important landmark in the story which today has nothing to denote it; the flow of the ice shelf and the accumulation of snow since 1912 have erased it from the geography, except as coordinates.

As it appeared in 1911.

Surgeon Lt. Edward Leicester Atkinson

There are people in this world who are rocks. They are never, in my experience, like stage heroes; they are nervy and highly strung. They do their best and seem to fail. And then comes some great emergency; and … [they] take a weight of responsibility which would crush hundreds of thousands of their fellow men. Not for an hour or a day or even weeks or months, but for an age which neither they nor anyone else know the limit, they carry on—cheering and comforting people to have about you when everything is going wrong—with a sense of duty which is beyond all praise. These men are rocks. I have never known a better rock than Atkinson was that last year down South. (Apsley Cherry-Garrard)

Read MoreMen of the Terra Nova

The story of the Terra Nova Expedition is epic and so uncannily archetypical, it feels like an adventure novel which has somehow escaped into reality. What really got me hooked on it, though, was the cast of characters. When I heard the radio play I couldn’t believe real people could be that wonderful; the more I learned about them the more wonderful they were. ‘The more you dig, the more gold you find’ was how a researcher friend put it, quite rightly.

It’s fascinating to go through the published journals and archives and see the same tale from everyone’s different point of view – each participant could be a protagonist in their own right – but I cannot do every version of the story so I am sticking mainly to Cherry-Garrard’s account, switching to another P.O.V. when necessary, as he does. Here is a rundown of the most important characters in that version of the story.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Despite his Oxford degree and sizable inheritance, what Cherry really needs is a purpose, and to prove his worth on his own terms. He is idealistic, observant, sensitive, and more naive than he realizes. Trapped by his high social status in civilization, on the Terra Nova he enjoys having a minor role in a great endeavour. The application of hard work to scientific advancement appeals to his idealism, and he finds kindred spirits among the specialists and naval officers, especially in the fatherly mentorship of Wilson and cheerful camaraderie of Bowers. As the Expedition knits into a family on the ocean journey, Cherry finds, for the first time, a vocation and a niche in a happy community, and is having the time of his life.

Dr. Edward ‘Bill’ Wilson

On Scott’s first expedition, Wilson was a junior doctor and keen amateur artist. He grew to be Scott’s right-hand man, and on the Terra Nova is Head of Scientific Staff and official Expedition Artist. Spotting a fellow idealist and nature lover, he invited Cherry to be his assistant; together they handle the zoological record. For Wilson, science and faith are two sides of the same coin: his spiritual side is private, but his rock-solid foundation makes him confidant, mediator, and role model to one and all. But he’s no stick in the mud – he joins in the roughhousing and banter with as much gusto as anyone, and is much loved by all who cross his path.

Lt. Henry ‘Birdie’ Bowers

Everlastingly cheerful and energetic, and apparently indestructible, this voyage to the polar regions is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream for Bowers, and his enthusiasm is infectious. His fiery red hair and enormous nose earn him the nickname ‘Birdie.’ This unpretentious exterior holds a heart of finest gold and a genius for organization, so he rapidly becomes one of Capt. Scott’s most valued officers, as well as a friend of everyone on board.

Captain Scott

With the weight of the Expedition on his shoulders, Scott initially comes off as grumpy and remote – certainly in comparison to schoolboy Evans. It is soon evident that he cares very much about those under his command, and his strengths as an experienced and capable commander come to the fore in times of difficulty, so the loyalty of those who served under him on his previous expedition is understood.

Charles Wright

A good-natured cynic from Toronto, Wright is going to Antarctica to further his study of radiation. As a Canadian, he is ribbed for being a Yankee and gets the nickname “Silas” as that's the most American name Birdie can think of. He takes this in (mostly) good humour, and despite his wry comments he's an eager participant in the Terra Nova family.

Lt. Edward ‘Teddy’ Evans

Apparently a bottomless font of bounce and charisma, Lt. Evans is officially Scott's second-in-command and has charge of the ship for its journey down the Atlantic. His task is to turn the motley collection of scientists and sailors into a capable crew, which he does through parlour games and horseplay as much as high-seas seamanship.

Lt. Harry Pennell

Officially the ship's navigator, Pennell is interested in everything, learns quickly, and lends a hand in every capacity. He finds happiness in work, and works all but the four hours a day he cedes to sleep, so being “happy as the day is long” he is very happy indeed.

Dr. E.L. ‘Atch’ Atkinson

The Expedition's chief medical officer, Atch is warm and caring under his nonchalant exterior. When not tending to the crew's physical complaints, he's deep in the guts of Dr. Wilson's latest specimen, hunting for a new species of parasitic worm. Surprisingly, no one shares this enthusiasm.

Terra Nova in a Nutshell

I have dived into telling you about my own Antarctic trip, but I haven’t yet told you the historical story which got me sufficiently interested in the place to get there myself. When I am taking friends through the Polar Museum I usually take about 90 minutes (plus oxygen break) to go through the whole story, but I will try, here, to keep it as concise as possible with liberal illustrations, and will expand later if you like.

The British Antarctic Expedition 1910 was under the command of Capt. Robert Falcon Scott, who had commanded a previous expedition to Antarctica in the Discovery in 1901-4. Officially the second-in-command was Lt. ‘Teddy’ Evans, but in all other respects it was Scott’s comrade from Discovery days, the doctor, naturalist, and artist Edward ‘Bill’ Wilson. His assistant on this second expedition was an idealistic young man named Apsley Cherry-Garrard, soon nicknamed ‘Cherry.’

Scott’s ship the Terra Nova left Cardiff on June 15th, 1910, had a very exciting and fun-filled journey to New Zealand and thence to Antarctica. She made landfall there in January of 1911, at a little outcrop of land on Ross Island which was christened Cape Evans.

While the hut was being constructed, Scott and a selection of men – including Wilson, Cherry, quartermaster ‘Birdie’ Bowers and seemingly indestructible sailor Tom Crean – set off to cache stores along the route to the South Pole, so that on the following year’s attempt to reach this geographical point they wouldn’t need to haul everything they needed from base. This string of depots culminated in one called One Ton Depot. On their way back to base, Cherry, Bowers, and Crean were crossing sea ice back to Ross Island when it broke up, and only by sheer pluck managed to get to safety instead of drifting out to sea. (I have made a 12-page comic about this episode, called The Sea Ice Incident, which you can download free if you want to know more.)

Shortly after this, Scott learned that Roald Amundsen, who was making a surprise attempt on the Pole himself, had also set up his base on the Ross Sea coast, in direct competition with Scott. As nothing could be done about this, Scott decided to proceed according to plan and not make a race of it. (He wasn’t happy about it, though.)

The first winter was a happy one, but for Cherry, Wilson, and Bowers, the conviviality of the hut was interrupted by a gruelling midwinter journey to the other side of Ross Island in search of Emperor penguin eggs, as part of Wilson’s investigation into the birds’ evolution, a trip they just barely survived.

R-L: Wilson, Bowers, and Cherry, after they’d been cut out of their ice-encrusted clothes on returning from Cape Crozier.

Three months later they set off again in the party of twelve who were to make the attempt at reaching the South Pole. It was arranged that two parties of four would successively turn back after helping the final four as far as they could. Cherry was selected to be in the first returning party, Lt. Evans headed up the second returning party, and Wilson and Bowers accompanied Scott in the final Pole Party. Cherry was disappointed to have turned back so soon, but got on with life back at the hut, happy to have played his part in the great endeavour.

The First Returning Party, returning.

All was well until news came that the leader of the second returning party, Teddy Evans, was deathly ill with scurvy. The expedition doctor, Atkinson, was supposed to go meet the final party with the dog teams as they returned, but was instead sidelined into caring for Evans. Atkinson delegated the rendezvous to Cherry, who duly took the dogs out to One Ton Depot to meet his friends, but they never turned up; he waited as long as he could, but as winter was closing in and he was running out of food for the dogs, he turned back to base.

When the Pole Party failed to arrive in the next few weeks, it became apparent that they never would, and the remaining men faced another winter knowing that their friends had perished. The following summer, another southern journey was made, in search of any trace of the Pole Party. They were expected to have fallen down a crevasse somewhere en route, but were found snowed up in their tent about twelve miles south of One Ton Depot, a point they had reached nine days after Cherry had turned back from there. From their letters and journals, the survivors learned that the Pole Party had reached the South Pole, but had discovered there that Amundsen had beat them to it by a month.

Four of the five members of the Pole Party, pictured with Amundsen’s tent.

On the return journey, two of the five men Scott had taken to the Pole suffered crippling mishaps, but instead of abandoning them, the healthy men slowed their pace. The injured men both eventually died, but by then the season had started to turn, and the remaining three – Scott, Wilson, and Bowers – were trapped in their tent by a blizzard which kept them from reaching the necessary food and fuel until they, too, expired.

The search party retrieved all the records and personal effects they could, then collapsed the tent over the Pole Party where they lay and built a great memorial cairn over them. They brought their story back to a world which, having been expecting great news, instead plunged into mourning.

Cherry had his own personal torment beyond that, though, in the idea that, had he pressed on with the dog teams from One Ton, he might have been able to save his friends’ lives. After returning to civilisation (and a small interruption we know as the First World War) he wrote The Worst Journey in the World, his memoir of the expedition, largely as a tribute to them and the friendship they’d shared.

A good portion of this book – the part relating to the Southern Journey – was adapted into a radio play in 2008, which is what got me hooked on the story (and especially the characters!) and precipitated the chain of events which got me out of animation and onto this crazy journey of my own, making the book – ALL of it – into a series of graphic novels. The BBC occasionally reruns the radio play, but you can more reliably listen to it here: https://archive.org/details/WorstJourneyInTheWorld01

Make Your Own Mits

One of the iconic visual cues of early polar exploration is the white H over the chest made by the straps of the fur mits. Here is the outfit they have on display at the Polar Museum in Cambridge:

I knew that I would be doing a lot of sketching in the cold and that I would need a way to warm my hands quickly and accessibly. Having large external pockets would also be handy (ha ha) for storing erasers and cameras and other things that lose their functionality too much below freezing. So why not make myself some good old fashioned polar mits?

Originally they were made of dog (or wolf) skin, which is still vastly preferred to artificial furs in Arctic communities. The long glossy guard hair repels moisture, and the soft undercoat provides insulation. There is a stall on Cambridge market which sells various skins and leather goods, even reindeer skins sometimes, but not dog (or wolf, or fox, or any canid) pelts, so the closest I could get was a wool fleece. This promised to be warm, if not as waterproof. The fleece had been brushed so it was incredibly fluffy and at least twice as long as the dog fur would have been, which may be a help or a hindrance, we shall have to see. I found a piece in their remnants bin which was large enough to make two mits. Not having sinew to sew them with, I found the nearest alternative:

Cutting the thumb pieces separately allowed for more efficient use of the material.

I sewed them together inside-out, so that I could see what I was doing and simultaneously squeeze the fluff inside and make them easier to pack in my suitcase.

In my years in Vancouver, I was spoiled rotten by easy access a magical emporium of all things sewing-related, which could supply anything you wanted and quite a few things you didn’t realise you needed until you step in for something else and find that a bag of odd buttons and a bolt end of nice jacquard are definitely urgent necessities. I can’t count how many times I’ve been working on something since moving away, and thought ‘Oh – if only I could go to Dressew!’ Aside from everyday supplies, Dressew has supplied me with several Halloween costumes’ worth of material; in fact, the costume I was working on in LA when I first heard the Worst Journey radio play was made from material I’d picked up the last time I’d been in Vancouver.

I did that again making these mits: I could have used readily available cotton twill tape for the lanyard, but if I was going so far as hand-stitching raw fleece I might as well do the thing properly and get the heavier stuff. If only I could go to Dressew! . . . But I COULD go to Dressew! I would be passing through Vancouver on my way to Antarctica! And so, with great joy, the day after I arrived . . .

[cue Heavenly Chorus]

I mean, just look at this place!

They didn’t have the exact type of lampwick that I thought I remembered from the SPRI mits, but I found some heavy cotton webbing that was close enough to serve the purpose. I took it back to my friend’s place where I was staying and brought the mits to completion, then turned them fur-side out again.

As the wool is so long, they look a bit like I’ve gutted a pair of Muppets or run off with the polar bear skin from the wall of the SPRI lecture theatre, but I can attest from just having them on my lap that they are plenty warm. I may need to take in the lanyard slightly as I have only guesstimated the thickness of the parka which will cause them to sit higher around my neck, but that is easier to do than lengthen. And I have a spare foot of webbing left over which might come in handy.

(So to speak.)

It occurred to me, while stitching cotton to sheepskin in the late October sunshine, that this is not a million miles removed from the Halloween costumes I’d be making every year around this time. My costume choices grew increasingly esoteric and ambitious until I gave up making them, but this one outstrips them all, and is going to be tested to the extreme of practicality. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work – the pockets on the ECW parka serve just fine for everyone else, so I have that to fall back on – but I’m looking forward to giving it a try.

Oh, and . . .

I couldn’t help it.

Antarctic Clothing on a Shoestring

The US Antarctic Program supplies the Extreme Cold Weather (ECW) clothing for its visitors – parka, snow pants, ‘bunny’ boots, balaclava, etc, as seen here – standard issue gear which they know is of a high enough quality to keep their participants warm and safe. I, however, have to bring everything that goes under that, and while I am happy once again to be living somewhere that has winter, even the rawest January in Cambridge, with winds straight off the North Sea, doesn’t quite necessitate the same extent of clothing as the start of Antarctic summer.

I am lucky enough to have a mother who grew up on the Canadian prairie long before such technological clothing as is pushed for such conditions now, so the wisdom of how to dress practically and cheaply for extreme cold was instilled in me from a young age. A tight layer just next the skin, then fluffier layers to trap air, and a heavy layer on top. A bit of extra room in your shoes is preferable to that extra layer of socks if the latter would restrict circulation. Mittens are better than gloves as your fingers can keep each other warm. From my Antarctic reading since then, I can add: breathability is paramount, as trapped perspiration will ice up and negate the warming qualities of your clothes. Layers are necessary to adjust for changing internal and external temperatures (very important when one is exerting oneself). For the outer layer, a lighter fabric which is windproof is preferable to a heavier fabric which is not; the warmth comes from layering up underneath. Seal up the openings at wrists, ankles, and neck to prevent draughts and snow getting in.

For my own sake, I wanted to stick with natural fibres as much as possible, mainly because I find them more comfortable, but also for the sake of environmental responsibility and durability.

Now, I have been a big fan of wool since discovering, on moving to Vancouver for college, that wool is just about the only thing that keeps out damp cold. When the voices of experience were unanimous in favour of plumping for merino long underwear, therefore, I happily concurred and stocked up; it was the most expensive part of my kit, but I figured the thermal layer was where I ought to make the investment. Upper layers of clothing won’t need changing as they don’t come in contact with skin and sweat, so it was more important for me to have multiples of the base layer than anything else; not only will they be interchangeable, but they can be layered as well. The local outdoorsy shop had a convenient sale, but I also scored some heavier high-end stuff second-hand on eBay, which I’m hoping will be comfortably snug.

Soft, antibacterial, machine-washable, biodegradable; wool is nature’s gift to shivery humans

I have a body shape which was last fashionable in about 1880, so finding trousers that fit properly is always a challenge. Usually I solve this by wearing skirts, but a freezing windy wilderness is not an ideal skirt location, so I had to figure something out. To my surprise and disappointment, the charity shops in Cambridge were not replete with tweed, nor in fact any woollen trousers at all; I did find some promising corduroy, but for wool I decided to gamble and buy online.

My sister, who has more refined taste and more expensive experience, once gave me the tip that higher-end clothing lines often fit ‘classic’ body shapes better, so when some 100% wool Jaeger trousers came up on eBay I gave them a shot and lo, she was right. As I can’t even afford to breathe the air in a Jaeger shop it was a fun and unexpected way to make a connection with Antarctic heritage, as some of the men brought Jaeger kit with them in 1910 and spoke highly of it then. We will see if their 21st-century ladies’ trousers rise to the same standard.

Finally, a charity shop did provide a pair of baggy, light, windproof trousers which I will wear overtop the warmer layers. Their waist needs taking in to preclude draughts, but otherwise I think the layering theory will hold.

The autumnal chunky wool ones didn’t make the cut when it came to the final packing.

Of equal importance to thermal layers is proper footwear – ‘look after your feet and they will look after you.’ I needed some new hiking boots anyway, so was hoping I could buy a pair that would do double duty on the ankle-turning rocks of McMurdo and the country walks I love in the UK. But the outdoorsy shop was clearing out last year’s boots in anticipation of new stock, and there was a deep discount on some Seriously Warm Boots, so I erred on the side of caution, trying them on with two pairs of thick socks to get the fit right.

‘Those are Seriously Warm,’ said the shop attendant, ‘you’d better be going somewhere cold.’

‘Antarctica,’ I replied.

‘Hmm, yeah, that counts.’

Who knows, they yet may prove to be multi-purpose if/when I move back to Canada at some point in the future.

I had a few pairs of warm socks already, but it was a good excuse to buy a few more, as well as some high-wool-content tights to supplement the merino leggings. One can never be too careful with one’s feet, as Captain Scott would like to remind us.

My advisor was adamant that I not bring any thick sweaters, saying it was far better to layer multiple lighter ones. Being already a fan of wool, I was not short on these, but I did take the excuse to find a couple more to replace ones that didn’t fit securely enough around the middle, where I am prone to draughts.

If you have recently moved to a cold damp climate, are of a female persuasion, and are looking to stock up on woollen outerwear, let me give you a tip: men’s sweaters. Women’s clothing is designed to be flattering, whereas men’s clothing is designed to be warm, which means a proper thickness and length sufficient to cover one’s hips, even when one is doing something so unbecoming as raising one’s arms. You may not look like a million bucks, but you will be enjoying your own body heat so much you may not even notice.

For the top layer, a good friend and comrade on the graphic novel front was letting go of a jacket I’d coveted several years ago, and thankfully let it go in my direction – high wool content, again, tightly woven and with a windproof lining. When I inspected the label, I discovered it was designed in Denmark and manufactured in Poland, which might explain why it’s so much warmer than anything I found in England. Being well-loved already means that I have the freedom not to be precious with it, so I might sew extra pockets on it or make other adjustments as the need arises.

Any resemblance to the Terra Nova’s ‘pyjama jackets’ is purely coincidental.

The promised ECW parka will be my outermost layer, of course, but it will be pretty chilly in both Vancouver and Christchurch before it is dispensed to me, so I am also bringing my very old friend, a gaberdine trenchcoat with a removable fleece lining. When I moved the the UK I had to choose between this coat and my heavy wool one, and have not regretted the choice; it’s shabby and unflattering but extremely hard-wearing and warmer than anything else I’ve owned, and while I’ve had to mend most of its seams at least once, the fabric itself has held up well against the fifteen years of abuse I’ve given it. I waterproofed it again before I left, and mended it again on the plane. I never would have guessed it would come with me to Antarctica, but this coat has earned it.

They say you can’t make old friends … but you can mend them.

I will also be supplied with various garments to keep my hands warm, when I arrive at the Clothing Distribution Center in Christchurch, and I am sure they will do the job. I do, however, have slightly unusual requirements in that I’ll be sketching in the cold, so need a way to warm my hands quickly and accessibly without fumbling through my layers. Frankly, the old explorers’ fur mits looked like the best way of solving that problem, so I set out to make some, to the extent that I could. That project will be the subject of the next post.

The Medical

We could pretend at planning all we liked, but no Antarctic plans could officially be made – especially plans that required outlay of money, such as airfare – until I had passed the Physical Qualification.

When Apsley Cherry-Garrard was applying to join the Terra Nova Expedition, he was told to turn up at the Expedition offices ‘prepared for a full medical examination.’ Presumably it all happened in one go. Mine was … not like that. I know that most people reading this blog are looking for entertainment, but perhaps you are preparing to undergo the same gauntlet. For your sake, dear grantee, I have tried to frame my experience as advice.

The US Antarctic Program’s medical screening is overseen by the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. After I had passed some invisible threshold in the process in April, they sent me a packet with instructions for obtaining the information they wanted to see. A full medical examination was part of it – every orifice was to be probed, many labelled ‘NOT DEFERRABLE’ – as well as a cursory eye exam, extensive blood tests, and a dental exam with complete X-rays.

Me and my frienemy, the PQ packet

The instructions for completing one’s medical stressed getting it in as early as possible, as the small team of doctors is swamped with applicants late in the summer when deadlines are tight. So, as soon as I got my packet, I started making appointments. The dental was taken care of within a week. To my surprise, given the moaning about NHS wait times, I got the necessary appointments booked all within the month of May. Everything seemed to be going well until the very last appointment, an ECG, which turned up a slight aberration in my heartbeat. My doctor said she couldn’t sign off the packet until it was unequivocally proven this wasn’t a health risk … so instead of mailing in my packet at the beginning of June as I had planned to do, I sat on it all the way through July so that I could have a full barrage of cardiovascular tests. These all came out clear, thankfully, so in the first week of August my packet was signed and FedExed to Texas. I avidly tracked its progress online and breathed a sigh of relief when it arrived, unimpeded by hurricanes or protests. Thank goodness that’s over with!

Ha, ha.

When the packet was received and examined, it was found wanting; the general pattern to the requests – which trickled in over several weeks, rather than all in one go – highlighted the fact that the packet had been designed by an American institution, to be completed by American doctors, and there were some important assumptions made which the British system didn’t pick up on. Resolving these discrepancies took six weeks of phone calls, hunting down paperwork, and rushing last-minute procedures.

Addenbrooke’s Hospital and Biomedical Campus, destination of many a hasty bike ride

So, should you be facing your PQ in the States, my advice is this: Book your appointments early, and be advised that probably none of this will be covered by your insurance, as your swanning off to Antarctica is completely elective. The NSF doesn’t cover it, either. It ain’t gonna be cheap, but it will probably be less than a commercial cruise to the Ross Sea. Probably.

If you are applying from the UK, or any other country with a similar single-payer national health system, here’s the scoop:

As per the above, book your appointments as soon as possible, because you never know what follow-up will be necessary. Additional incentive to haste is that everyone goes on holiday in July and August, so getting hold of a doctor or secretary becomes much harder as the summer goes on.

Socialised medicine is a boon and a blessing but it is not tremendously accommodating of elective procedures being done on a tight deadline. Your blood tests and specialist follow-ups, being of minimum medical urgency, go to the end of the queue. This is great for the person who needs prompt diagnosis of leukaemia, say, but not you.

As this is all elective, you will have to pay privately. Most GPs in the UK offer private appointments, but you may find speedier service at a private clinic. It will probably cost the same anyway. Again, it’s not cheap, but it’s cheaper for you than for someone in the States, so count your blessings.

The medical board want to see every bit of data that led your doctor to approve you for Antarctic travel. This means including printouts of all your blood test results, your ECG, and records/receipts for any new vaccinations in the packet you send to Texas. If you have had any medical issues in the last few years, or been tested for anything serious at all even if the results were negative, they want to see the paperwork for those too. In the NHS, some of this paperwork requires special permission to access, for which you must apply, and it might take a month to process. On the other hand, you may get lucky by phoning the original clinic and explaining your situation to the right people. Everyone thinks going to Antarctica is really cool. Sometimes strings can be pulled.

On the NHS, the tetanus/polio/diptheria vaccine does NOT come with the pertussis vaccine included, which the USAP requires. You must find somewhere that will give you the pertussis-inclusive bundle, either a travel clinic or a private GP. Pertussis does not come on its own so there’s no point getting the regular booster until you find a source for the all-inclusive one.

Blood type is not on the checklist in the packet because it’s standard in US blood tests, but the NHS does not ascertain or record your blood type as a matter of course. You must tell your doctor that you need your blood group and Rhesus factor determined as well as all the other tests, otherwise you will have to get another blood test on short notice and wait for the results all over again.

If UTMB want supplemental documents, they will only accept physical mail or faxes. Posting something to the US is too slow, and couriering a succession of documents may bankrupt you, but you can send a fax online from gotfreefax.com – it’s free up to three pages and pocket change for more. They take PayPal. It’s much easier than finding a fax machine.

Having received my packet in April, I only got passed by the medical board on 21 September. I’d had to gamble on booking international flights to get to the US jumping-off point, because if I waited until I had PQ’d, the point at which I officially joined the programme, airfares would have been ridiculous.

Cherry was accepted onto the Terra Nova Expedition two days after his examination and interview, five weeks before the ship sailed from London. In spite of my vastly longer lead time, I passed my PQ four weeks and five days before my flight out of Heathrow. Sometimes those 109 years between us seem very thin.

It was an anxious summer, and there were times I sincerely doubted I would get to go at all, but back in August I decided that it would take more effort to prepare for the best than the worst, so I started amassing some of the recommended clothing and the gear I planned to take with me. Next time: Antarctic Shopping!

The Spectrum of Selection

It was May 31st, 2018 that I submitted my application to the Antarctic Artists & Writers Program.

The automatic confirmation of receipt said that it would be a few months before I heard anything. That was all right. I had lots to do. That summer I was busy writing the script, designing characters, and assembling a mental model of the Terra Nova from photographs, shipwrights’ plans, written records, and the model of the ship at SPRI, none of which quite agreed with each other. In September I took off to visit the Discovery in Dundee, to get a working knowledge of the interior of a polar ship of that period, for which scant record of the Terra Nova survives.

November I was teaching; December I finally started thumbnailing page layouts. On December 21st, Antarctic Midsummer, I got an email telling me that my proposal was ‘highly competitive’ and I was shortlisted for the AAW’s 2019/20 season.

The next day, the US government shut down.

The first time I had looked into the Antarctic Artists & Writers was 2009. I had read Sara Wheeler’s Terra Incognita, a travel book largely consisting of her time with the USAP on said programme in the ‘90s, and I looked up what it would take to get into it myself. But this was the height of the financial crisis, and austerity was biting deep into government spending; the AAW website said the programme was on hiatus, with no indication of when, or if, it would return.

Now here we were again, with the whole US Antarctic Program waylaid by politics. As the shutdown dragged on into January with no sign of resolution in sight, I began to wonder if the AAW would be happening at all this year. But, as the snowdrops in England began to bloom, the crossed stars over Washington aligned, and a little while after government business resumed, I got another email from the USAP asking to arrange a video conference. Things were back on track.

Somehow, despite never getting an explicit announcement that I’d made the cut – and indeed several insistent messages that nothing said hereunto constituted a commitment on the part of the USAP – we began to proceed as though I were going South. I once again outlined the scope of my project, what I was bringing and what locations I needed to visit. One long teleconference saw an enormous packet of resource requests filled out – again, the sort of thing geared towards scientists, but I put in requests for everything from crampons to helicopter hours. I applied for a permit to visit the protected historical sites. This was all shepherded by my most able and indefatigable point of contact with the Antarctic administration in Colorado. I’m pretty sure she never took time off.

All this paperwork was contingent on passing the infamous Physical Qualification; having the forms and applications filled out in advance meant that, once that was approved, everything could slot into place and hit the ground running. I would not be officially added to the USAP’s season roster, however, until I had PQ’d.

The medical packet arrived in April; the saga of fulfilling it to the satisfaction of the medical board deserves a post all of its own.

The Fun and Joy of Grant Applications

A spot on the USAP’s Artists & Writers crew is, in effect, an NSF grant. One is not paid for one’s time there, but it is no insignificant expense on the part of the National Science Foundation to house one, feed one, and move one around a continent of ice. Therefore, the application process is just as rigorous as if I were an astrophysicist going down to study cosmic rays, and the paperwork and procedures were identical.

The primary thrust of the application was to convince the NSF that I was For Real, that my project was going to reach a large number of people, and that it was relevant to the work being done in Antarctica now.

Points 1 and 2 were easy enough; my years at Disney and classical drawing portfolio were sufficient to qualify me as a legitimate professional artist, if not high culture. I was lucky enough to get in on the ground floor of the fanart phenomenon, so I’ve got a comparatively large and loyal following online. But how to communicate the relevance of a bunch of Brits* a hundred** years ago to the US Antarctic Program’s current endeavours?

Well, quite simply, they were doing the same science in the same places, and laying the foundation for all the work that would come after them, whichever country was doing it. The main American base, McMurdo Station, is a stone’s throw from where Scott’s first expedition put down roots. The expedition I’m interested in – Scott’s second – was based fifteen miles north of there, but the environment was much the same, and by Antarctic standards that’s just next door. They weren’t Americans, but they were humans, doing the same meteorology, magnetology, physics, marine biology, glaciology, geology, zoology, and any number of other -ologies on the same species, ice, weather, sea currents, rocks etc. as the humans there now. It is one continuum of science which spans nearly the entire period of human activity in the Antarctic.

My main point, though – one which I made when my obsession was young, and one I will continue to make while there is breath left in me – is that the best way to make people care about something is to tell them an emotionally engaging story about it. I like science; I watched a lot of nature documentaries as a child; even so, I had only an abstract appreciation of Antarctica as a piece of relatively pristine nature which, of course, we should preserve. Since getting emotionally attached to the Terra Nova Expedition, I will defend the Antarctic Treaty to the death. If only a small proportion of my readers are affected the same way, who knows how that might nudge future Antarctic policy? Perhaps even more importantly, readers might develop an emotional interest in a branch of science via the entertaining and lovable character doing that science as part of the story. How many people went into archaeology because of Indiana Jones, or crime scene forensics because of CSI? Glacial flow rates and frazil ice are a lot more interesting when you can associate them with a wisecracking Canadian with an unprintable vocabulary.

As the application process is the same for both artists and scientists, there were a lot of forms that needed filling out which bore little or no relevance to my projected work – I didn’t need to list possible radioactive or biohazard materials I’d be working with, or arrange cargo delivery by ship, or request access to specialist equipment. The budget sheet was refreshingly simple to complete as it consisted entirely of zeroes. But every form needed filling, and then submitting through quite a complicated website, and sometimes reformatting when the PDF scanner thought it had too many headings, or when it turned out the budget sheet needed a 1 somewhere in order not to confuse the computers.

Despite the heavy childhood consumption of PBS, I grew up in an environment which was highly skeptical of government science grants. The general assumption was that publicly funded scientists were living high on taxpayer dollars, and would make up spurious studies to further their cushy careers. Having now done, once, what scientists have to do all the time just to stay employed, I cordially welcome all skeptics to try it for themselves, and try to imagine living on the amounts generally awarded, which have to cover equipment and lab costs as well as living expenses. As a nerdy child, science was held up to me as a secure and profitable career choice vs. starving in a garret; in retrospect, the arts has given me a better life and a happier savings account than most scientists I know.

Writing the application, which included making a few new illustrations to communicate what the finished project would look like, took most of May 2018. The deadline was June 1st. I set aside the last week for the submission process alone, which was just as well as the day before the deadline it looked like I’d have to be registered as an independent vendor to the US government, a process which could take at least two weeks. Then it turned out I was using the wrong website to submit. I got the paperwork in just as the gates were closing, and thus began the long wait to find out if my efforts would pay off.

* Plus one Canadian, one Norwegian, two Australians, and two Russians

** 109 years now, but who’s counting

Before the Adventure Begins

In November of 2019 I will be going to Antarctica with the US Antarctic Program’s Artists and Writers initiative, which takes a handful of creatives down to the US bases in Antarctica to get the word out about the science being done down there, and increase public awareness of the Southern Continent.

The journey to being able to write that in black and white on the Internet has been a long one, so before I go, I thought it would be good to give a little bit of the background story …

In 2008, shorty after the biggest breakthrough in my animation career, I heard a radio dramatisation of The Worst Journey in the World, about the doomed British attempt to reach the South Pole in 1912. I liked it very much. I like lots of radio plays. But this one wouldn’t let me go. When I finally exhausted the play itself, I read the book it was based on, which led to three more, then ten, and within a year or two I was dangerously verging on ‘expert.’ (This is the short version. The long version, with pictures, can be found in The Best Journey in the World.)

(Spoiler: It was even more awesome.)

It occurred to me, while drawing at my desk listening to the radio play for the umpteenth time, that this story would make a very good graphic novel. For some reason, no one had done it yet. The centenary of the expedition approached, and yet still no graphic novel appeared. As I accumulated historical knowledge and craftsmanship, I started to wonder if perhaps I was becoming the most qualified to do such a thing. But this was mad! I had a good job in animation and no experience in comics; who was I to take on that project?

Well, long story short, within a few years I had abandoned my career and moved to Cambridge to make it happen. As I write this, I am now halfway through drawing Vol. 1 of the graphic adaptation of The Worst Journey in the World, with the permission and encouragement of the Scott Polar Research Institute. I have spent so many hours in the archives that I can recognise the handwriting of these long-dead men like a familiar voice. I’ve chased their traces from England and Scotland to Canada and New Zealand. I’ve sketched and photo’d many of their objects, all but physically reconstructed their ship, and I have 812 historical photographs on my phone, where pets or children should be.

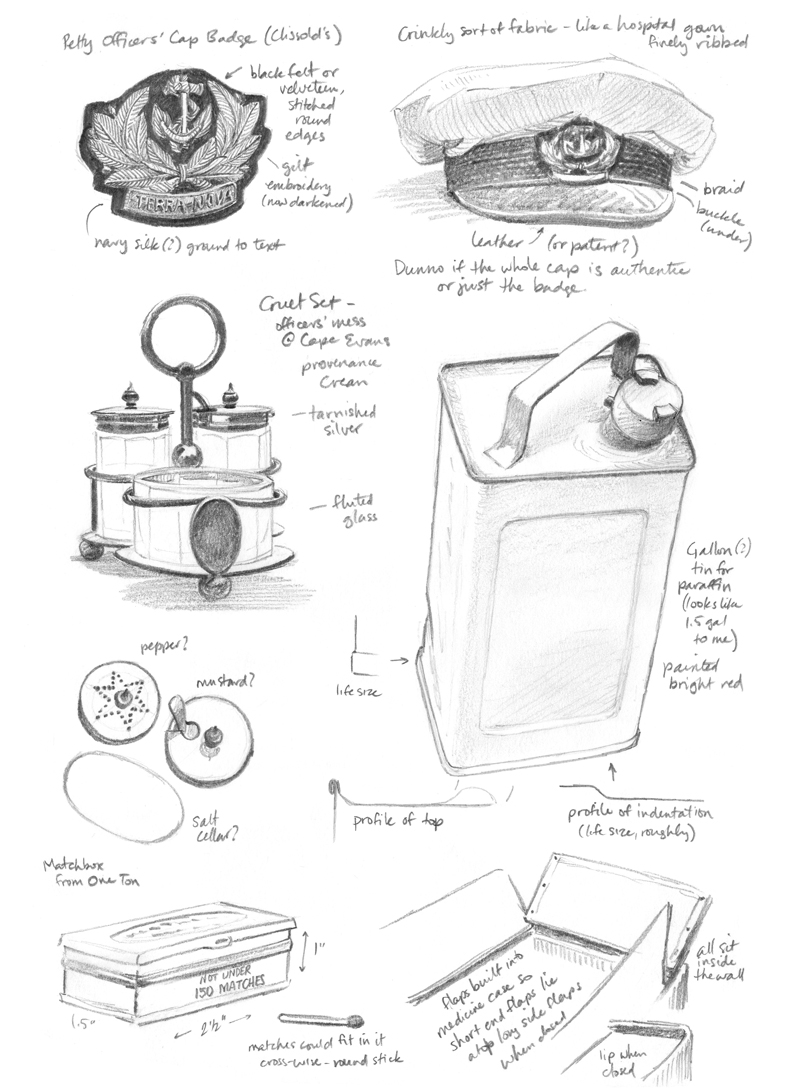

Objects at the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, NZ

But what I kept hearing from everyone more expert than me was that one really must go there to understand it properly. Do whatever you can to get there. It will all make so much more sense if you do. There is nowhere else like it in the world.

How was another question. Most everywhere I turned, I ran into some impediment of circumstance, nationality, or price. The USAP program dangled, temptingly, but I thought, in comparison to the people who have gone in the past, I am neither a Serious Writer nor a Real Artist – would they consider spending their precious time and resources on someone drawing cartoons of dead people? And they aren’t even American dead people! What does the British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13 have to do with the United States Antarctic Program in the 21st century?

Quite a lot, in fact, but that is a matter for the next post . . .

DIY Life Drawing

A very keen young animator in London, frustrated with the lack of drop-in animation-friendly life drawing on offer, has set up a life drawing club – the price for 3+ hours good solid gesture drawing is taking your turn to go up and pose (clothed).

Black Stilt

Brush pen, Monterey Bay Aquarium, December 2013

![[map taken from the British Antarctic Survey website]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5205b8f0e4b04f935ee86748/1572367325017-LQCLTKGUJRS6TVNVZGP6/antarctica-macro.jpg)

![[base image taken from Google Maps satellite view]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5205b8f0e4b04f935ee86748/1572368540994-WRXDIDEOGLZ38KKNMJWK/rossis.jpg)

![[cue Heavenly Chorus]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5205b8f0e4b04f935ee86748/1572134179980-PETU775L0IJS5IDXCCL0/dressew.jpg)