On this flight to the heart of Antarctica, I was only a hanger-on. We had two errands to run before entertaining me and my historical interests, the most important of which was restocking a fuel depot at the base of the Transantarctic Mountains.

There are many busy science teams in Antarctica, and while some renewable energy sources are starting to be used, the fact is that everything runs on a reliable supply of fossil fuels, mostly petrol. The aircraft that keep people and their essentials moving around the continent have a network of fuel depots, both for relay stops and for emergencies. Contrary to some conspiracy theories, anyone can fly to and around Antarctica if they have the money and resources to get there, and many do. As the national science programmes have a very tight margin, and their fuel depots are expensive to maintain, they cannot afford jet-setters raiding their supplies, so the locations of these depots are kept secret. Therefore I am not going to tell you where our first stop was. The chances of a private pilot reading this blog are slim, but it may be possible to deduce from my photos where this particular cache is: if you are that outlier, I hereby ask you please to do the decent thing and leave the fuel alone – or if you absolutely must access it, then let the USAP know what you've taken and make good on it as soon as you can. Everyone in Antarctica looks out for each other, and that includes you. OK? OK.

So, we've taken off, and done our acrobatics to get the skis up, and are now facing a couple of hours' flight time before we reach our primary destination. There is, quite frankly, nothing between Williams Field and the Transantarctic Mountains, besides hundreds of miles of the Ross Ice Shelf. This was known as 'The Barrier' to the early explorers, because when James Clark Ross sailed down to explore in 1840 it was a great while wall that prevented his ships from going any further. In later years it wasn't so much a barrier as a highway – clear and flat, and not much off sea level, it provided a route deep into the high latitudes without the perils of the high windy Polar Plateau. Among people who frequently travel out there, it is sometimes referred to as 'the Flat White' – my impression is that this term came from the Kiwis, and the espresso drink of the same name is also antipodean in origin, so I wonder which came first. It is undeniably Flat, and White (though the refraction of sunlight through ice crystals makes it look anything from peachy to periwinkle, depending on the angle), but none of its various names communicate just how big it is.

I have flown over the Canadian tundra many times, and over the Greenland ice cap, but the view from 35,000 feet is like looking at satellite view in Google Maps compared to flying at cloud level, where the parallax with the horizon gives you a much keener sense of distance. The Barrier is BIG. In fact, 'big' is too small a word to communicate it. 'Massive', 'mammoth', and 'gargantuan' are more melodramatic than descriptive. Its vastness puts all of human consciousness, never mind vocabulary, in proper perspective. For my money, it outdoes the night sky as a visual approximation of infinity.

Getting a sense of its size, especially in a still photo, is difficult without an object for scale. For your education and my good fortune, we happened to fly over the RAID convoy as they made their way from the Minna Bluff site to where the Ross Ice Shelf meets the Antarctic continent. Rapid Access Ice Drilling has been supporting various scientific projects for a few years now, whether their interest is in the ice itself (its trapped air gives a record of Earth's atmosphere in millennia past) or what's underneath (marine environments far removed from the open sea; the bed of an accelerating glacier). Their units are about the size of a shipping container, and are pulled by enormous tractors, so if they are this dwarfed by the Flat White, imagine how much more puny a sledge party would be.

Before too much longer we were at the depot. Landing at an Antarctic field airstrip is even more complicated than taking off: we circled once, to do a visual check, then skimmed it with the skis to make sure no hidden crevasses had opened up since the last time someone landed here, then finally touched down for real on the third go-round. The plane crew rapidly got to work unloading the fuel drums; I offered to help but was assured I wasn't needed, so spent the time taking photographs and mucking around in the snow.

The first thing that struck me was how beautiful the mountains were in colour. The best photos I've seen of them have been black and white, so the rich variety in shades was remarkable. What you can't see in this small photo was how the lighter rock was banded with strata of blue-grey and orange-brown sandstone, giving it a luxurious marbled effect.

I've read a lot about how conditions on the Barrier are so much different than on the coast. This was far deeper into it than I was ever expecting to set foot, but I was surprised how tame it was. Now, it was an idyllically calm and sunny day – had it been any different we would not have been there – so the only time I realised that it was actually much colder than McMurdo was when a slight breeze wafted past my bare hand and broke the warm spell that the sunshine had cast.

What was different was the snow. Around McMurdo, the snowbanks which did build up had been repeatedly blown over with volcanic dust which warmed up in the sun and made the snow gritty, icy, and rotten – if you live in a snowy city, think of the texture of snowbanks alongside busy roads. Out here, there was nothing but snow, all the way down to where it became ice – powder blown off the mountains, maybe even off the Polar Plateau, deposited here to be compacted in the sun and polished by the wind. The crust made by these processes was smooth and, in many places, thick enough to support my weight, so I hardly left a footprint – a 'good pulling surface' as sledgers would have it – but without warning there would be a thin spot where my foot would break through and sink in the sugar-like snow below.

Tracks left by the Basler's landing gear. Without an object for scale, they might be sledge tracks, or crevasses, who could say?

Before long, the crew had finished their restock, and playtime was over. After our exciting takeoff manoeuvres, we started climbing the mountains to the second of our tasks for the day.

The Transantarctic Mountains, according to our pilot, are still something of a mystery. They are a very high mountain range, but unlike the Rockies for example, they show little or no sign of buckling or other geological forces – they seem to have been lifted whole, keeping their layers of sandstone and coal and fossil-rich deposits mostly flat, with occasional intrusions of igneous rock. The range acts as a sort of massively oversized dyke, holding back the miles-deep polar ice cap from spilling over West Antarctica, the Ross Ice Shelf, and the Ross Sea, as the mountains cross the continent.

Ice appears to be solid, but it actually behaves more like a stiff jelly or fondant icing – if it finds a change in altitude it will flow, very slowly, downhill. This is what a glacier is: snow gets deposited over many years without melting, turns to ice, and when its volume can no longer be held at elevation, starts to creep down the valley. The ice of the Polar Plateau finds gaps in the Transantarctic Mountains and pushes through them, forming glaciers which pour out onto the Ross Sea and, merging, form the Ross Ice Shelf. The Beardmore Glacier is one of the largest of these, but there are hundreds of smaller ones, and many tributary glaciers that feed these. In flying over the lower Transantarctic Mountains, there were plenty of opportunities to see ice dynamics at work:

Look, it flows!

Our destination was up near the head of a narrow glacier, where it broadened out into a snowy plain called the Bowden Névé – névé being a term for young snow which has not yet compacted into glacial ice but is in a position to do so. This was CTAM (pronounced see-tam), a geology camp established to be a hub for teams doing work in the Central TransAntarctic Mountains. The névé afforded an open, soft, flat place to land planes carrying supplies and people, who could then move on to less accessible places overland. At least, it did, until a wind event a few years ago scoured deep furrows in the landing strip.

As we flew over, doing the visual check, I was astonished the site could be spotted at all, as it was only a small clutch of bamboo poles in the vast expanse.

I did recall, eventually, that GPS is a thing. I may be spending too much time in the present, lately, but some parts of my brain are permanently stuck in 1910.

It was such a wide plain, and so magnificent a vista, that I thought it was the Beardmore at first.

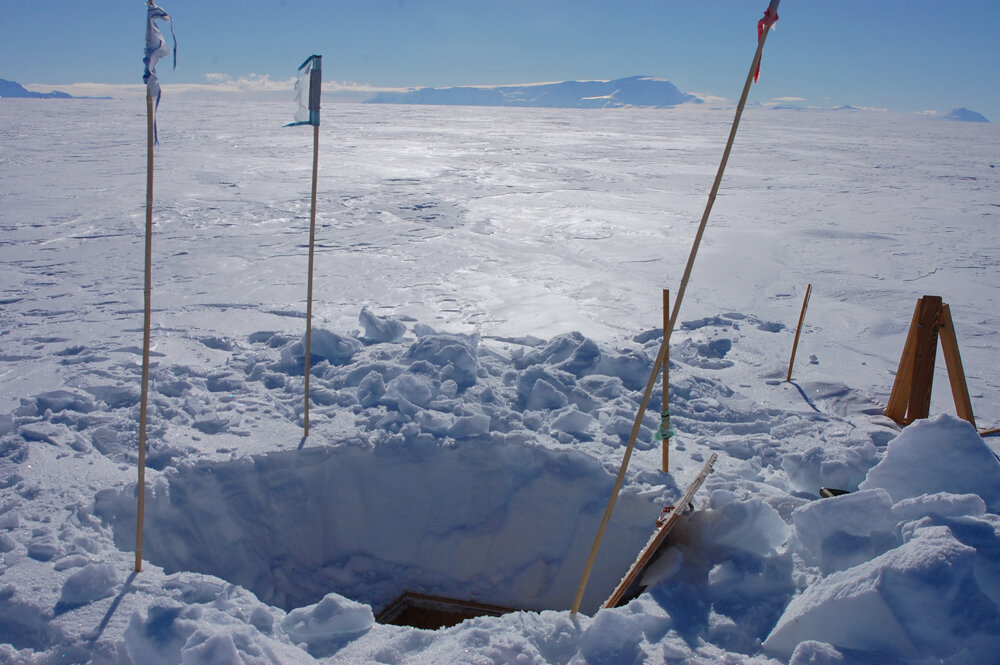

Having proven that the landing strip was landable, the next task was to see what condition the building was in. What building, you ask? Why, the one completely covered in snow, under the markers. Once upon a time it was a couple of modules standing on the surface of the glacier, but Antarctica gradually swallowed them up, so now one has to dig down through the snow to reach the roof hatch, eight feet above the floor.

On the way from the Basler to the camp site, I was treated to one signature snow effect I had missed out on, at the depot. 'The Barrier Hush' is frequently mentioned in journals: it was described as a 'whoosh' or a 'hush-shh-shhhh' that sighed out from underneath the walker as he broke through the top crust into a pocket of air underneath, where the loose snow had settled after the top crust was formed. The pocket could sometimes extend quite a long way from where the crust was broken and the sound followed the exchange of air as far as it went. It would startle the ponies and excite the dogs, until they learned there was nothing to chase and catch.

I was walking some way behind the plane crew as they made for the camp with shovels, and suddenly heard what I thought was a small whirlwind – a sharp and intense, almost whistling sound that seemed to race across my path. This being the sort of place one would expect to see dust devils (or snow devils, I suppose they would be) I looked around to see where it was, but the air was as still up here as it had been down on the ice shelf. It was only after the second or third time it happened that I realised what it was – it was so completely not how I had imagined the Barrier Hush to sound. If you make a little whirlwind sound by whisper-whistling whshwshywshwhwwsh with your lips really quickly, that's what it sounded like. Having heard it, now, I can completely understand how the dogs would have thought there was a small creature scurrying around under the snow. It sounded much more animate than it had been described. I felt so lucky to be let into that secret.

The crew got the hatch open and the first of them climbed down into the pitch darkness to report everything OK. The rest followed, and invited me along, but I am not the most coordinated travelling artist, and couldn't see a way down for me that didn't end in a concussion. So I stayed above while they explored the submerged camp, and enjoyed the view. It was really spectacular – not just the stunning mountains but the thin, brittle blue of the sky and the hardness of the sunlight, as if the whole world were a taut drumskin.

And, best of all, from here the horizon was the Polar Plateau – another Flat White stretching to the South Pole and beyond.