You may have noticed that last week I breezily mentioned a visit to Scott's Discovery Hut as though it were just another class on the schedule. It most definitely was not! Wandering around one of the principal locations of the Terra Nova Expedition – of the whole of Heroic Age Antarctic history – was the pinnacle of the sensory overload of my first 36 hours on the continent, not least because the grubby old Discovery Hut is one of the least well documented sites, so most of it was completely new to me. To visit the other locations on my itinerary, I needed one or another sets of training, but Hut Point is only a short walk from McMurdo Station on solid ground, so my coordinator was keen to get me there as soon as possible.

My first full day in Antarctica was the coldest of the whole trip. I noted in my journal that it was -4°F/-20°C – I don't recall if that was with wind chill or without, but it was definitely windy that day, so you can imagine. The previous day's flurries were still blowing around, so the atmosphere was properly polar, and for the first time I was glad I had brought the heavy-duty boots that had been such a boulder in my luggage.

Some members of Antarctica New Zealand visit Vince’s Cross (a memorial to seaman George Vince, who died nearby on the Discovery Expedition) at the promontory just down Hut Point from the Discovery Hut.

The Discovery Hut is named such because it was built on the Discovery Expedition, in early 1902 when the ship had found its permanent berth in the small bay at the end of the southernmost peninsula of Ross Island. The bay was imaginatively dubbed Winter Quarters Bay, and the spit of land adjacent to it was called Hut Point, the creativity of which was extended to the whole Hut Point Peninsula. The hut itself had been picked up in Australia, where it was a flat-pack prefab intended to be transported to the Outback and used to house cattlemen as they drove herds across the country. As such, it was designed to shed heat – not an ideal feature in an Antarctic dwelling, but it was never intended to be lived in, rather to serve as a warehouse and emergency shelter should anything happen to the ship. Subsequent expeditions used it more than the Discovery did, because of its proximity to the permanent ice of the Barrier, which made it a key staging point for any southward travel. They all complained of it being uncomfortably cold inside.

The Hut and RRS Discovery in winter quarters, with the two iron-free auxiliary huts (now gone) for magnetic work. McMurdo Station is now built on the gentle slope you see behind the Discovery’s masts. Photo from the Royal Society collection.

And it was cold. Not that I noticed much, beyond corroborating historical reports that it somehow seemed colder inside the hut than outside. Antarctic cold is a funny thing: You are certainly aware that it is cold, but it is a surface sensation only, and doesn't feel as severe as the thermometer says it is. Skin exposed to the air registers the fact it is cold, but even at -20 it didn't go any deeper than that. Compared to the seeping, insidious cold of a damp British morning or an air-conditioned animation studio cubicle, which disregards layers and seems to chill you from the inside out, -20 in Antarctica is really quite comfortable, if you're dressed properly and sheltered from the wind. I barely noticed how cold it was until the tips of my gloved fingers started tingling, which I observed with some perplexity until I remembered the temperature. At that moment I understood how one could get frostbite without noticing, because one's outermost extremities could suffer while one's internal thermostat was still reading as perfectly warm, if not hot. Hence the practice of deliberate, conscious reminders every few minutes to observe the state of one's feet – they would be all too easy to overlook, otherwise.

Lithium ion batteries don't much like the cold, and unlike human bodies they neither generate their own heat nor have a core heat bank to rely on. I got a few photos that first visit, but my phone died as I was taking a video, so I decided to leave the image harvest to another day. The photos in this post are mostly from later (warmer) visits, when electronics were functioning fully and I'd got over the initial awe of being there.

But before I can give you a photographic tour of the Discovery Hut, I need to fill you in on the history, so that you know what you're looking at when you see it, as I did.

As I said before, the hut was built during the Discovery Expedition but hardly used except for storage and, occasionally, a theatre. The next expedition in town was Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition, which arrived in early 1908. The sea ice that year was much more extensive than it had been in 1902, and the furthest south that the Nimrod could anchor was at Cape Royds, twenty miles north of Hut Point. Shackleton had been on the Discovery, though, and knew there were a lot of good things left in the little square hut across the ice, so he sent a raiding party to scavenge some of them and bring them back to Cape Royds. When they arrived, they couldn't get the door open, so they broke a window to get in, which was never repaired. After it had served its purpose as launching point for southern journeys and the Nimrod left McMurdo Sound, the hut filled up with drifted snow which compacted into ice.

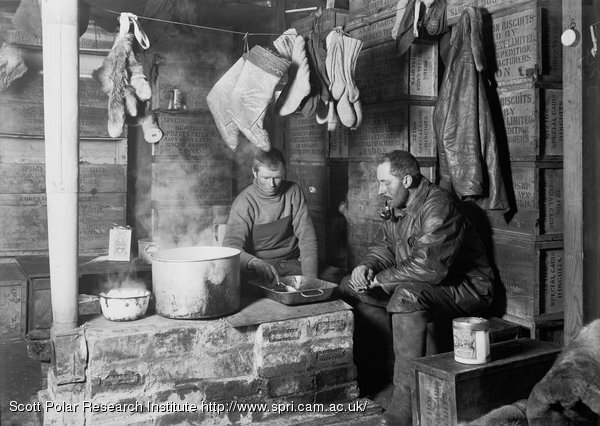

When Scott arrived in the Terra Nova – which was also barred from Hut Point by sea ice and so had settled at Cape Evans, fifteen miles north – he found the broken window and the interior of the hut one solid block of ice. This did not do much to improve his opinion of Shackleton. The depot-laying party pushed on south with their supplies, but Atkinson, who had got an infected blister on his heel and couldn't continue marching, was left at Hut Point with Tom Crean; while the depot party was away, they employed themselves in clearing the ice from the hut. Once that was done, they used biscuit cases and the discarded winter awning from the Discovery to build a smaller chamber within the single room, which would hold the heat better, and improvised a blubber stove from discarded bricks and metal in the Discovery's rubbish heap. There are lots of seals around Hut Point so blubber was a self-supplying fuel, as opposed to the very limited quantity of coal which had been brought down by the ship.

Dmitri Gerof (L) and Cecil Meares (R) at the blubber stove in the Discovery Hut, 1911

The only way to reach Cape Evans from Hut Point is over the sea ice, and by the time the depot party returned, that had all broken up and gone out to sea. (I am glossing over The Sea Ice Incident. Check it out if you want some crazy adventure.) There was nothing for it but to wait at Hut Point for the sea ice to freeze again, which took from the beginning of March to the middle of April. This was, as yet, the longest period of occupation for the hut, and was full of tinkering to make the place more liveable. Everyone devised what they thought was the best model of blubber lamp: whatever the design, it smoked with a thick black soot which added to the smoke from the blubber stove. As a result the hut was often thick with smoke and everyone looked like chimney sweeps before long. Crean and Atkinson had done a massive job clearing out the block of ice in the main room, but there was still ice in the cavity between the ceiling and the roof which they could not access, and this dripped on the assembled crowd every time they got the hut above freezing, turning their reindeer skin sleeping bags into a soggy mess. Despite the soot, the 'snipe marsh,' and a diet limited to recombinations of biscuit, seal meat, and the odds and ends left over from previous expeditions, the men all had a roaring good time. Some of them even claimed, when all was said and done, that this was the best part of the expedition.

Just enough to eat and keep us warm, no more – no frills nor trimmings: there is many a worse and more elaborate life. The necessaries of civilization were luxuries to us: … the luxuries of civilization satisfy only those wants which they themselves create.

— Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World

The hut served its purpose again the following November as the jumping-off place for the great effort to reach the Pole. This is its classic role, and what it is best remembered for, when it is remembered at all, but something which I think gets lost and which adds a great deal to the emotional understanding of the place is that it's also the first taste of home for returning parties, the first solid walls after months of living in a tent. For both the First and Second Returning Parties it was a concrete assurance that they had made it, they were back to safety; it was only the matter of a day's walk to Cape Evans from there, which they did all the time. Like reaching one's own freeway exit after a long road trip, the Discovery Hut would be a welcome return to the familiar. It's the first comfort the Polar Party would have been pulling towards in their struggle to get home before the weather broke up for the winter.

But, as we know, they never got there. The next role of the Discovery Hut, and its most poignant, to me, is as the staging point for another southward journey, the one to meet the Polar Party with the dog teams. Atkinson had taken the dogs there after using them to help unload the ship at Cape Evans, but before he could leave he was co-opted to save the life of Teddy Evans , leader of the Second Returning Party, who was dying of scurvy not far away. Atkinson had to find a substitute, so he sent a message to Cape Evans requesting Wright, and if he was unavailable, Cherry-Garrard. Simpson, who was in charge back at Cape Evans, sent both to Hut Point, with the advice that Wright was needed for his particular scientific expertise and that it would be very inconvenient to lose him. So Wright was sent home, and Cherry was chosen to go south. He failed to meet the Polar Party; he and the dogs turned up back at the Discovery Hut exhausted, frostbitten, and unable to do any more work that season. Cherry spent a miserable purgatory in the hut with a strained heart and broken wrist, delirious on painkillers and tormented by the howling wind and fighting dogs, gradually coming to realise that his friends were never coming home.

When the Terra Nova finally left Antarctica for good, they left a large depot of food at Hut Point for whoever might come after, an act of generosity whose prescience was not long in the proving. Shackleton's Endurance Expedition is famous for the ship getting crushed in the ice and the last-chance boat voyage to South Georgia to find rescue. Fewer people know that that expedition had another half: a smaller contingent of men were sent to the Ross Sea to lay depots for the Endurance party to pick up as they crossed the Antarctic continent, which was the expedition’s original raison d’etre. They had what can only be described as a mindblowingly horrible time. It started with their ship being blown off its anchor at Cape Evans and out to sea before it had been fully unloaded, and got much worse from there. Winter clothing had to be improvised from a heavy canvas tent left by the Terra Nova Expedition, and they depended largely on the food that had been left at Cape Evans and Hut Point two years previously. By supreme effort they succeeded in laying the depots required of them, all the way to the Beardmore Glacier over 400mi/600km to the south, and suffered terribly from scurvy on the way back, one of them dying. The remainder narrowly scraped their way into the safety of the Discovery Hut, to recover their health and wait for the sea ice to freeze, but two decided prematurely that the greater comfort of Cape Evans was worth the risk, and set out over the new ice, never to be seen again. It turned out that their suffering was entirely in vain, as the Endurance party, whose survival they expected to depend on their depots, never so much as set foot on the Antarctic continent.

The view to Cape Evans from the end of Hut Point. Cape Evans is the smudge at horizon level, leftmost of the three long low shapes at upper centre. The sea ice here is walkable, despite the cracks; in May of 1916 it was not.

These are the layers of history with which the Discovery Hut, and all the geography of McMurdo Sound, are imbued. It was one of my great privileges, while a guest of the USAP, to be a portal to the Heroic Age for many people who were mostly unaware of what had passed before the building of the American station. It's harder to transmit the tangible immediacy of the history via the internet, but I hope this and the next post will get you some of the way there.